Notes and quotes from Huey Newton’s autobiography

- February 17th, 2012

- By agentofchange

- Write comment

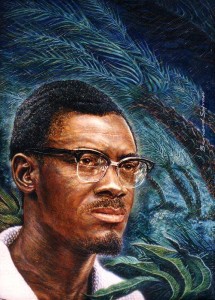

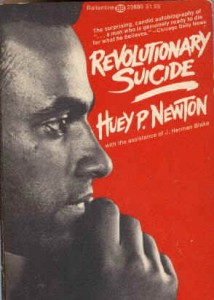

Since today is the 70th anniversary of Huey P Newton’s birth, I thought I’d share some of my thoughts on his autobiography, ‘Revolutionary Suicide’. In my opinion, Revolutionary Suicide is a crucial contribution to the field of revolutionary strategy and tactics, particularly for those working in the ‘belly of the beast’ – the imperialist countries of Europe and North America.

Since today is the 70th anniversary of Huey P Newton’s birth, I thought I’d share some of my thoughts on his autobiography, ‘Revolutionary Suicide’. In my opinion, Revolutionary Suicide is a crucial contribution to the field of revolutionary strategy and tactics, particularly for those working in the ‘belly of the beast’ – the imperialist countries of Europe and North America.

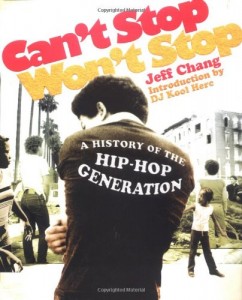

What made the Black Panther Party and affiliated black/brown power organisations so special? What made them stand out from the myriad of other radical/progressive/socialist organisations? I think the main thing is the fact that they were able to mobilise the *masses* – they were able to move beyond the usual middle-class left dogmas and outdated methodology (“fanning our flames to the hurricane”, to use George Jackson’s vivid expression) and really engage oppressed people in the struggle for their own freedom. Yes, they were smashed by the state; yes, many mistakes were made; but nevertheless they made unprecedented gains which we should actively learn from.

If you haven’t read it yet, I’d strongly recommend you to read ‘Revolutionary Suicide’, along with Huey’s ‘To Die For The People’, Bobby Seale’s book ‘Sieze the Time’, Assata Shakur’s autobiography and Mumia Abu Jamal’s ‘We Want Freedom’. That’s a minimum Panther reading list. Trust me, it’s worth it!

In terms of learning from Huey’s ideas about building a revolutionary movement, I think the following points from ‘Revolutionary Suicide’ are some of the key things for us to consider:

- BUILD UNITY THROUGH REAL STRUGGLE. Learning to fight the oppressor is the way to stop fighting each other. Huey communicates this idea by relating the story of how, at his high school, the black students created unity in response to the dominance of white racist gangs.

- BUILD UNITY THROUGH SHARED GOALS. Nobody agrees on everything, and yet left organisations insist on defining themselves on the basis of petty differences with each other. Work out a basic platform and move on it.

- BUILD A SENSE OF COMMUNITY. Modern capitalism takes away our sense of community, of togetherness, or shared purpose. It promotes individualism and fear. Any revolutionary organisation or movement must seek to build unity and cooperation in the communities it works within. Socialism is built from the ground up.

- BUILD ALTERNATIVE EDUCATION. The education system fails oppressed people. It teaches self-hate and subservience. The revolutionary must be an educator. Raising consciousness is a long-term, arduous, essential project and needs constant attention.

- MOBILISE AMONG THE MOST OPPRESSED. Although the traditional US left was focusing its attentions on the industrial working class, the Panthers realised that this was not the most revolutionary class in society, as it had largely been bought off and was enjoying the fruits of imperialism and racism. Huey points out that a revolution must be built on the basis of those elements in society that have nothing to lose; that are ready to go against the system.

- REVOLUTION STARTS NOW. Meet the survival needs of the people, in the here and now. Build power in the communities. Take responsibility. Political power doesn’t drop from the skies; it is built in real life, and that process begins now with the fight for survival. “Revolution is not an action; it is a process.”

- ACTION SPEAKS LOUDER THAN WORDS. You can’t engage people with a load of talk and dogmatism. Find ways to get the attention of those people you want to revolutionise. Be relevant, be visible, get people moving in the struggle for real goals. No left-wing organisation that I know of in Britain gets anywhere near to this, as they have no roots in oppressed communities and therefore are not on the right wavelength.

- BE RELEVANT. You don’t have to dumb down your ideas to be acceptable to the masses; you don’t have to take ‘popular’ positions; but you *do* have to be relevant. Many groups fail because they are completely divorced from the masses, and because they adopt an alienating, doctrinaire, superior attitude in relation to oppressed people.

- STUDY THE ART OF REVOLUTION. Learn how others have developed movements and won freedom, and let their strategies inform yours.

- BUILD YOUR OWN PLAN. While learning from others, remember that your struggle has its own unique characteristics, and therefore you must develop your own unique strategy based on a deep analysis of concrete conditions, rather than relying on blueprints or dogmas.

- FIGHT THE POWER. Develop the skills to deal with the system on a daily level. Know your rights – with police, in school, with bailiffs etc. This is key for building pride, confidence and solidarity.

- THE OPPRESSED MUST LEAD. Organisations have a definite need for people with what Huey calls “bourgeois skills” – middle class radicals with good writing, computer, administration skills etc. In many organisations unfortunately these skills bring leadership status to those that have them. This should be avoided!

Here are some quotes I thought were worth typing out:

On being a revolutionary

“I will fight until I die, however that may come. But whether I’m around or not to see it happen, I know that the transformation of society inevitably will manifest the true meaning of ‘all power to the people.'”

“By surrendering my life to the revolution, I found eternal life”

“The first lesson a revolutionary must learn is that he is a doomed man. Unless he understands this, he does not grasp the essential meaning of his life.”

“The oppressor cannot understand the simple fact that people want to be free. So, when a man resists oppression, they pass it off by calling him ‘crazy’ or ‘insane'”

“You can only die once, so do not die a thousand times worrying about it.”

On building a movement

“We discussed Mao’s program, Cuba’s program, and all the others, but concluded that we could not follow any of them. Our unique situation required a unique program. Although the relationship between the oppressor and the oppressed is universal, forms of oppression vary. The ideas that mobilised the people of Cuba and China sprang from their own history and political structures. The practical parts of those programs could be carried out only under a certain kind of oppression. Our program had to deal with America.”

“Che and Mao were veterans of people’s wars, and they had worked out successful strategies for liberating their people. We read these men’s works because we saw them as kinsmen; the oppressor who had controlled them was controlling us, both directly and indirectly. We believed it was necessary to know how they gained their freedom in order to go about getting ours. However, we did not want merely to import ideas and strategies; we had to transform what we learned into principles and methods acceptable to the brothers on the block.”

“To recruit any sizeable number of street brothers, we would obviously have to do more than talk. We needed to give practical applications of our theory, show them that we were not afraid of weapons and not afraid of death. The way we finally won the brothers over was by patrolling the police with arms.”

“Mao and Fanon and Guevara all saw clearly that the people had been stripped of their birthright and their dignity, not by any philosophy or mere words, but at gunpoint. They had suffered a holdup by gangsters, and rape; for them, the only way to win freedom was to meet force with force. At bottom, this is a form of self-defence.”

“We came to an important realisation: books could only point in a general direction; the rest was up to us.”

“Interested primarily in educating and revolutionising the community, we needed to get their attention and give them something to identify with.”

“It was my studying and reading in college that led me to become a socialist. The transformation from a nationalist to a socialist was a slow one, although i was around a lot of Marxists. I even attended a few meetings of the Progressive Labour Party, but nothing was happening there, just a lot of talk and dogmatism, unrelated to the world I knew. It was my life plus independent reading that made me a socialist – nothing else.”

“The street brothers were important to me, and I could not turn away from the life I shared with them. There was in them an intransigent hostility toward all sources of authority that had such a dehumanising effect on the community. In school the ‘system’ was the teacher, but on the block the system was everything that was not a positive part of the community.”

“[When we started patrolling the police] many community people could not believe at first that we had only their interest at heart. Nobody had ever given them any support or assistance when the police harassed them, but here we were, proud Black men, armed with guns and a knowledge of the law. Many citizens came right out of jail and into the party, and the statistics of murder and brutality by policemen in our communities fell sharply.”

“If we developed strong and meaningful alliances with white youth, they would support our goals and work against the establishment”

“Too many so-called leaders of the movement have been made into celebrities and their revolutionary fervour destroyed by mass media. The task is to transform society; only the people can do that – not heroes, not celebrities, not stars. A star’s place is in Hollywood; the revolutionary’s place is in the community with the people.”

“Revolution is not an action; it is a process.”

“The survival programs are a necessary part of the revolutionary process, a means of bringing the people close to the transformation of society.”

“The Breakfast for Children program was set up first. Other programs – clothing distribution centres, liberations schools, housing, prison projects, and medical centres – soon followed. We called them ‘survival programs pending revolution’, since we needed long-term programs and a disciplined organisation to carry them out. They were designed to help the people survive until their consciousness is raised, which is only the first step in the revolution to produce a new America. I frequently use the metaphor of the fact to describe the survival programs. A raft put into service during a disaster is not meant to change conditions but to help one get through a difficult time. During a flood the raft is a life-saving device, but it is only a means of getting to higher and safer ground.”

“We had the base now on which to construct a potent social force in the country. But some of our leading comrades lacked the comprehensive ideology needed to analyse events and phenomena in a creative, dynamic way. We [formed the] Ideological Institute, which has succeeded in providing the comrades with an understanding of dialectical materialism. About three hundred brothers and sisters attend classes to study in depth the works of great Marxist thinkers and philosophers.”

“I dissuade party members from putting down people who do not understand. Even people who are unenlightened and seemingly bourgeois should be answered in a polite way. Things should be explained to them as fully as possible. I was turned off by a person who did not want to talk to me because I was not important enough. After the Black Panther Party was formed, I nearly fell into this error. I could not understand why people were blind to what I saw so clearly. Then I realised that their understanding had to be developed.”

“My experiences in China reinforced my understanding of the revolutionary process and my belief in the necessity of making a concrete analysis of concrete conditions. The Chinese speak with great pride about their history and their revolution and mention often the invincible thoughts of Chairman Mao Tse-Tung. But they also tell you, ‘This was *our* revolution based upon a cornet analysis of concrete conditions, and we cannot direct you, only give you the principles. It is up to you to make the correct creative application.’ It was a strange yet exhilarating experience to have traveled thousands of miles, across continents, to hear their words. For this is what Bobby Seale and I had included in our own discussions five years earlier in Oakland, as we explored ways to survive the abuses of the capitalist system in the Black communities of America. Theory was not enough, we had said. We knew we had to act to bring about change. Without fully realising it then, we were following Mao’s belief that ‘if you want to know the theory and methods of revolution, you must take part in revolution. All genuine knowledge originates in direct experience.'”

“We must never take a stand just because it is popular. We must analyse the situation objectively and take the logically correct position, even though it may be unpopular. If we are right in the dialectics of the situation, our position will prevail.”

On education

“During those long years in Oakland public schools, I did not have one teacher who taught me anything relevant to my own life or experience.”

“Throughout my life all real learning has taken place outside school. I was educated by my family, my friends, and the street. Later, I learned to love books and I read a lot, but that had nothing to do with school. Long before, I was getting educated in unorthodox ways.”

“The clash of cultures in the classroom is essentially a class war, a socio-economic and racial warfare being waged on the battleground of our schools, with middle-class aspirating teachers provided with a powerful arsenal of half-truths, prejudices and rationalisations, arrayed against hopelessly outclassed working-class youngsters. This is an uneven balance, particularly since, like most battles, it comes under the guise of righteousness.” (quote from Kenneth Clark, ‘Dark Ghetto’)

“Strong and positive influences in my life helped me escape the hopelessness that afflicts so many of my contemporaries. My father gave me a strong sense of pride and self-respect. By brother Melvin awakened in me the desire to learn, and because of him I began to read. What I discovered in books led me to think, to question, to explore and finally to redirect my life.”

“I knew right there in prison that reading had changed forever the course of my life. As I see it today, the ability to read awoke inside me some long dormant craving to be mentally alive. My homemade education gave me, with every additional book I read, a little bit more sensitivity to the deafness, dumbness and blindness that was affecting the black race in America.” (quote from the Autobiography of Malcolm X)

On community

“When people in the congregation prayed for each other, a feeling of community took over; they were involved in each other’s problems and trying to help solve them. Here was a microcosm of what ought to have been going on outside in the community. I had the first glimmer of what it means to have a unified goal that involves the whole community and calls forth the strengths of the people to make things better.”

“Among the poor, social conditions and economic hardship frequently change marriage into a troubled and fragile relationship. A strong love between husband and wife can survive outside pressures, but that is rare. Marriage usually becomes one more imprisoning experience within the general prison of society.”

“Those in the community who defy authority and ‘break the law’ seem to enjoy the good life and have everything in the way of material possessions. On the other hand, people who work hard and struggle and suffer much are the victims of greed and indifference, losers. This insane reversal of values presses heavily on the Black community. The causes originate from outside and are imposed by a system that ruthlessly seeks its own rewards, no matter what the cost in wrecked human lives.”

On prison

“The state believes in the power of euphemism, that by putting pleasant name on a concentration camp they can change its objective characteristics. Prisons are referred to as ‘correctional facilities’ or ‘men’s colonies’, and so forth; to the name givers, prisoners become ‘clients’, as if the state of California were some vast advertising agency. But we who are prisoners know the truth; we call them penitentiaries and jails and refer to ourselves as convicts and inmates.”

“I have often pondered the similarity between prison experience and the slave experience of Black people. Both systems involve exploitation: the slave received no compensation for the wealth he produced, and the prisoner is expected to produce marketable goods for what amounts to no compensation. Slavery and prison life share a compete lack of freedom of movement. The power of those in authority is total, and they expect deference from those under their domination. Just as in the days of slavery, constant surveillance and observation are part of the prison experience, and if inmates develop meaningful and revolutionary friendships among themselves, these ties are broken by institutional transfers, just as the slavemaster broke up families.”

“Many white inmates are not outright racists when they get to prison, but the staff soon turns them in that direction. While the guards do not want racial hostility to erupt into violence between inmates, they do want hostility high enough to prevent any unity. This is something like the strategy used by southern politicians to pit poor whites against poor blacks.”

“The whites are not only duped and used by the prison staff, but come to love their oppressors. Their dehumanisation is so thorough that they admire and identify with those who deprive them of their humanity.”

“The spirit of revolution will continue to grow within the prisons. I look forward to the time when all inmates will offer greater resistance by refusing to work as I did. Such a simple move would bring the machinery of the penal system to a halt.”

“James Baldwin has pointed out that the United States does not know what to do with its Black population now that they ‘are no longer a source of wealth, are no longer to be bought and sold and bred, like cattle.’ This country especially does not know what to do with its young Black men. ‘It is not at all accidental,’ he says, ‘that the jails and the army and the needle claim so many.'”

“The great mass of arrested or accused black folk have no defence. There is desperate need of nationwide organisations to oppose this national racket of railroading to jails and chain gangs the poor, friendless and black.” (Quote from WEB DuBois)

“The masses must be taught to understand the true function of prisons. Why do they exist in such numbers? What is the real underlying economic motive of crime? The people must learn that when one ‘offends’ the totalitarian state, it is patently not an offence against the people of that state, but an assault upon the privilege of the few.” (George Jackson, ‘Blood in my Eye’)

“Giving a prisoner a number is another way of undermining his identity, one more step in the dehumanisation process. Of course, it has historical roots: the SS assigned numbers to prisoners in Nazi concentration camps during World War II”

On Malcolm X and black consciousness

“White America has seen to it that Black history has been suppressed in schools and in American history books. The bravery of hundreds of our ancestors who took part in slave rebellions has been lost in the mists of time, since plantation owners did their best to prevent any written accounts of uprisings.”

“Malcolm X’s life and accomplishments galvanised a generation of young Black people; he helped us take a great stride forward with a new sense of ourselves and our destiny. But meaningful as his life was, his death had great significance, too. A new militant spirit was born when Malcolm died. It was born of outrage and a unified Black consciousness, out of the sense of a task left undone.”

“IQ tests are routinely used as weapons against Black people in particular and minority groups and poor people generally. The tests are based on white middle-class standards, and when we score low on them, the results are used to justify the prejudice that we are inferior and unintelligent. Since we are taught to believe that the tests are infallible, they have become a self-fulfilling prophecy that cuts off our initiative and brainwashes us.”

“As far as I am concerned, the party is a living testament to Malcolm’s life work. I do not claim that the party has done what Malcolm would have done. Many others say that their programs are Malcolm’s program. We do not say this, but Malcolm’s spirit is in us

“Malcolm X impressed me with his logic and with his disciplined and dedicated mind. Here was a man who combined the world of the streets and the world of the scholar, a man so widely read he could give better lectures and cite more evidence than many college professors. He was also practical. Dressed in the loose-fitting style of a strong prison man, he knew what the street brothers were like, and he knew what had to be done to reach them.”

On black nationalism

“All these programs were aimed at one goal: complete control of the institutions in the community. Every ethnic group has particular needs that they know and understand better than anybody else; each group is the best judge of how its institutions ought to affect the lives of its members. Throughout American history ethnic groups like the Irish and Italians have established organisations and institutions within their own communities. When they achieved this political control, they had the power to deal with their problems.”

“The most important element in controlling our own institutions would be to organise them into cooperatives, which would end all forms of exploitation. Then the profits, or surplus, from the co-operates would be returned to the community, expanding opportunities on all levels, and enriching life. Beyond this, our ultimate aim is to have various ethnic communities cooperating in a spirit of mutual aid, rather than competing. In this way, all communities would be allied in a common purpose through the major social, economy and political institutions in the country.”

“Blacks are a colonised people used only for the benefit and profit of the power structure whenever it suits their purposes. After the Civil War, Blacks were kicked off plantations and had nowhere to go. For nearly one hundred years they were either unemployed or used for the most menial tasks, because industry preferred to use the labour of more acceptable immigrants – the Irish, the Italians and the Jews. However, when World War II started, Blacks were again employed – in factories and by industry – because, with the white male population off fighting, there was a labour shortage. But when that war ended, Blacks were once again kicked off ‘the plantation’ and left stranded with no place to go in an industrial society.”

On China

“What I experienced in China was the sensation of freedom – as if a great weight had been lifted from my soul and I was able to be myself, without defence or pretence or the need for explanation. I felt absolutely free for the first time in my life – completely free among my fellow men. This experience of freedom had a profound effect on me, because it confirmed my belief that an oppressed people can be liberated if their leaders persevere in raising their consciousness and in struggling relentlessly against the oppressor.”

“The behaviour of the police in China was a revelation to me. They are there to protect and help the people, not to oppress them. Their courtesy was genuine; no division or suspicion exists between them and the citizens.”

“The Chinese truly live by the slogan ‘political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,’ and their behaviour constantly reminds you of that. For the first time I did not feel threatened by a uniformed person with a weapon; the soldiers were there to protect the citizenry.”

On democracy

“Institutions work this way. A son is murdered by the police, and nothing is done. The institutions send the victim’s family on a merry-go-round, going from one agency to another, until they wear out and give up. this is a very effective way to beat down poor and oppressed people, who do not have the time to prosecute their cases. Time is money to poor people. To go to Sacramento means loss of a day’s pay – often a loss of job. If this is a democracy, obviously it is a bourgeois democracy limited to the middle and upper classes. Only they can afford to participate in it.”